Alright folks, here we are: the sequel to the most popular newsletter I ever published. Once for 2022, and now again for 2023…

But first! Thank you all for another year of support. This newsletter’s become a pretty important part of my life, and the time you’ve gifted both it and me is greatly appreciated.

Alrighty then, here we go…

THE FOURTEEN BEST THINGS I WATCHED IN 2023 (because 10 is still boring)…

#14: Barbie (dir. Greta Gerwig)

I’ll be perfectly honest…there are a lot of things about Greta Gerwig’s billion-dollar-grossing story of plastic existentialism that didn’t sit well with me. I guess there’s only so much empty corporate feminism and Will Ferrell a heartless, joyless boy like me can take in one sitting. But there’s too much charm to this thing, too much imagination filling every frame, too many laughs packed into every corner, too many catchy tunes lining every inch of its two-hour runtime, for this to have left anything but a bright impression on my brain. And look at how much meaning Greta got out of these toys! Barbie discovering that life is more than the whims of old white guys? Ken discovering that he’s more than the love/anger he feels for a woman who doesn’t want him? Wonderful stuff. Look at it this way: there’s a reason I got a rainbow-colored “I am Kenough” hoodie for Christmas.

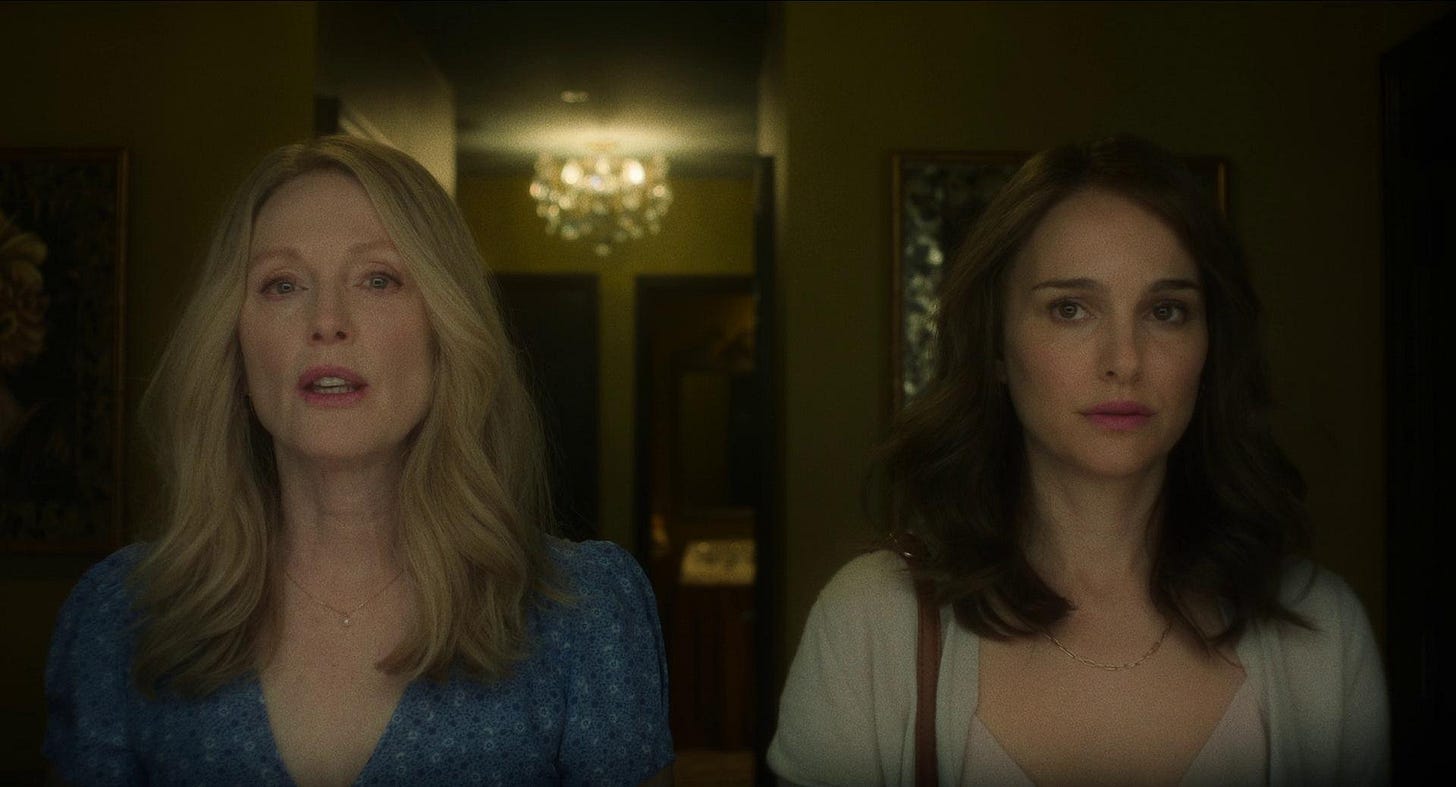

#13: May December (dir. Todd Haynes)

This one cuts like a diamond.

While I’m of the opinion that Hollywood should be allowed to churn out more than just one productively transgressive film a year, I don’t have any problem with May December being 2023’s. Concerning the seedy tale of a film star (Natalie Portman) as she integrates herself for research purposes into the lives of a couple once-infamous for their illicit, age-gap relationship (Julianne Moore & Charles Melton, their characters inspired by Mary Kay Letournau & Vili Fualaau), this is a movie as much about America’s bizarre fascination with true crime as it is about the extremely fragile relationships so many of us have with sex. It’s uncomfortable in the best possible ways, interrogating us as often as it interrogates its characters. It’s a brutal thing, a unique thing, constantly changing just like the monarchs Melton’s character nutures as a hobby. It moves when you least expect it; you like Portman’s character until you don’t, you dislike Melton’s until you don’t, you understand Moore’s until you don’t. It’s a detective story until it’s a relationship drama, a relationship drama until it’s a thriller film, and a thriller film until it becomes a heartcrushing satire. Or perhaps it’s none of these things; perhaps it’s just a tragedy, and the other prisms are just coping mechanisms for me to avoid the horrific sadness. Either way, there’s nothing out there quite like this.

#12: Spider Man - Across the Spider-Verse (dir. Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, Justin K. Thompson)

There’s not really anything I can say here that hasn’t been said in other, better places by other, better writers. Much like Everything Everywhere All at Once, this is a terrific, optimistic, idiosyncratic, alternate universe thing that everything loved just a smidge more than I did (and believe me, I still loved it). Feel free to read my newsletter about it that I wrote back in June. But if you’d prefer not to, I’ll say this: to watch Across the Spider-Verse is to be reminded that films can feel as alive as the person standing next to you. It’s to be reminded that this artform we all love is still young, still capable of learning new tricks, and still capable of blowing the rest of the competition out of the water. It’s the kind of movie that’ll remind you of the most special people you’ve ever met, that’ll almost make you jealous with how vibrant it is…and I can’t remember the last time a movie made me jealous.

#11: Mission: Impossible - Dead Reckoning Part One (dir. Christopher McQuarrie)

I guess it wouldn’t be a normal week here at Ronan Jensen HQ without Tom Cruise being mentioned. But I have to do it, because he produced & starred in what turned out to be the best action film that graced 2023’s summer (his best buddy Christopher McQuarrie directed, co-produced & co-wrote). While not as purely blissful as Mission: Impossible - Rogue Nation, or as earth-shaking as Mission: Impossible - Fallout, Dead Reckoning Part One still found its way into my heart. There’s so much fun to be had in its wildly imaginative set pieces, everything from a Fiat-filled, handcuffs-bound car chase through the streets of Italy to an absolutely fantastic climax set aboard an ill-fated locomotive careening towards doom…Mission once again delivers the crunchy, explosive, escapist goods. But how about a little extra? Yes: there’s even some prescient, frightening ideas at play here underneath all of the action, with Cruise’s nemesis this time around being an artificial intelligence threatening to throw the entire world into chaos. And who else is more fit to represent out inherent, often stupid, still-beautiful individuality than the one remaining Hollywood star willing to risk his life for big-screen glory?

#10: The Holdovers (dir. Alexander Payne)

What is it about the holidays that make so many of us feel so lonely? Maybe there’s body chemistry involved, the cold cranking our hearts into overdrive or something. Maybe it’s the constant lovey-dovey imagery we’re all collectively drowned in: the families clasping hands in front of enormous dinners, the cuddling couples warming themselves in front of fires, all of it making us feel like failures if we fall short. Whatever the reason, Alexander Payne’s The Holdovers dedicates itself to plaguing us with that horrific feeling of holiday-bound loneliness…and then re-dedicates itself to nursing us back to health with the power of the world’s greatest chicken noodle soup. Detailing the bonds between a curmudgeonly professor (Paul Giamatti), a pain-in-the-ass student (Dominic Sessa), and a grieving cook (Da’Vine Joy Randolph) as they’re forced to stay at a boarding school together during Christmas break, this is one of those wonderfully honest stories that doesn’t feel cheap when it inevitably warms your heart. Why? Because it makes sure to break it first, slowly but surely, into a thousand little pieces. But Payne (what an appropriate name) then takes the time to, if not put it all back together, show us that doing so is possible, so long as you’re careful…and not alone. Bonus: I had the joy of watching this with a good buddy of mine who’d (a) already seen it and (b) was enjoying the multiple beers he’d snuck into the theater. Honestly? There’s nothing better.

#9: The Fall of the House of Usher (dir. by Mike Flanagan & Michael Fimognari)

I don’t know what it is, but I have always been drawn to stories about sinners (usually male, I’ll admit) who are faced with the enormous weight of what they’ve done. Perhaps it’s the romantic in me, in love with the idea of a world in which actions have consequences, justice is real, and the things we do actually matter. Or perhaps it’s the penitent in me, seeing something I recognize in the ravaged faces of these dark, masculine characters. I wonder if Mike Flanagan (an admitted alcoholic) feels the same way. His latest project, the wonderful horror series The Fall of the House of Usher, follows billionaire pharmacuetical patriarch Roderick Usher (Bruce Greenwood, in one of the year’s finest performances) as he deals with the murderous fallout of a bargain he & his twin sister Madeline (Mary McDonnell) made on New Year’s Eve, 1980 with a mysterious stranger (Carla Gugino). You see, every single one of his many children (most of them bastards) are dying off in increasingly gruesome ways, with evidence of the stranger found at almost every single crime scene. And, while it may just be the effects of a decaying brain, poor Roderick is starting to see the ghosts of his offspring.

To watch a Mike Flanagan project is to be comforted as equally as you are challenged. His work is never soothing; they’re all horror stories, the warmth usually arriving only after his characters have been subjected to immense amounts of physical & emotional pain. But you can feel the love he puts into them, along with the love that every member of his cast-heavy Flanafamily dedicates right alongside him. And The Fall of the House of Usher is yet another testament to that love, every angry, guilt-ridden, gorgeously-camp minute of it. Besides: what can be more delicious than watching Bruce Greenwood recite Poe?

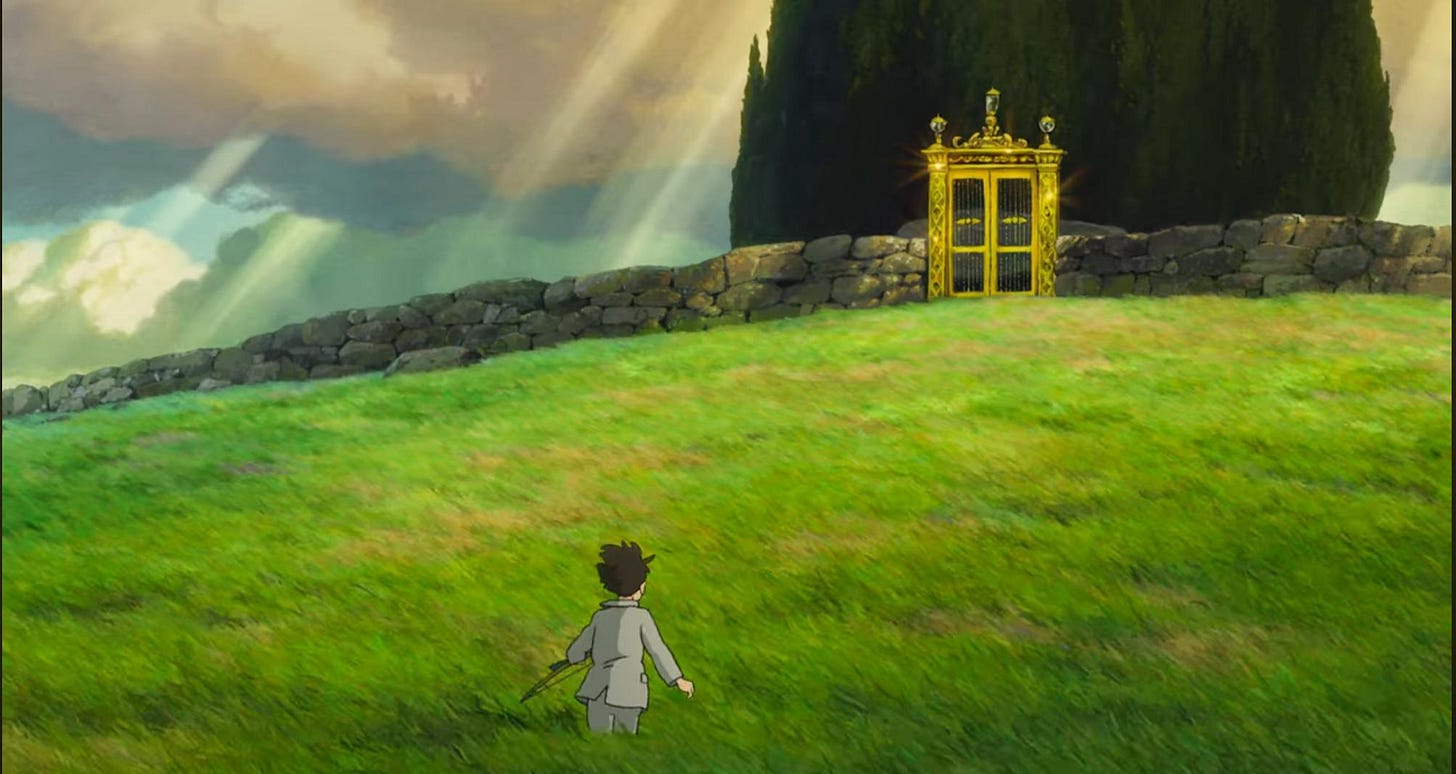

#8: The Boy and the Heron (dir. by Hayao Miyazaki)

Gorgeous. Mesmeric. Enchanting. A movie seemingly wise to everything that’s come before it, and yet somehow still excited for what might lay ahead…

Ten years. That’s how long it’s been since Hayao Miyazaki’s last film, an entire decade. It’s been too long, even though it was supposed to be much longer; “last movie” has more than one meaning here, because Miyazaki had announced to the world that he would finally retire after The Wind Rises was released back in 2013. But he’d made that threat before in 1997 after Princess Mononoke, then made it again in 2004 after Howl’s Moving Castle. It seems that not even a good man is capable of keeping himself down, because here we are once again. The Boy and the Heron has been advertised by Studio Ghibli as Miyazaki’s final film, the very last, we’re serious this time guys…but of course, it’s already been announced that the director has apparently returned to work, apron on and pencil in hand, his next project in the planning stages. Boredom must be the only thing more terrifying to Miyazaki than death.

Whether it is one or not, The Boy and the Heron certainly feels like a “last movie”, although that’s not to say it has a deathly sense of finality to it. This is not a funeral. On the contrary, it feels like Miyazaki (and his enormous team of collaborators) have shoved everything they possibly could into its 124-minute runtime. David Rees once said that every great movie tends to be “either a puzzle or a dream”; The Boy and the Heron is both. I’ve never seen anything quite like it. It’s a coming of age story made by a man who, at first glance, must have come of age decades ago...but perhaps there is no such thing as “coming of age”. Regardless, to define this movie with that term is to restrict it almost criminally; yes, it’s the story of a kid named Mahito (Luca Padovan) being led by a nefarious heron (Robert Pattinson, believe it or not) into an alternate world filled with humanoid birds and adorable, balloon-shaped spirits…but it’s also the story of an older man trying to pass his creations down to the next generation, the story of a woman struggling to become a mother, the story of a son mourning the death of his own mother…I could go on forever. I’ll end it with this: the well of churning, roiling emotion that The Boy and the Heron made me feel is something that few pieces of art have ever inspired in me before. If this is indeed the final work of Miyazaki’s career, I couldn’t think of a more worthy note to end on.

#7: The Killer (dir. by David Fincher)

It is a rare thing for a film to truly seduce the viewer, to aborb the entirety of their attention, and yet David Fincher seems incapable of doing anything but with his work. There are obvious reasons for this: his sleek craftsmanship, his infamous (and over-mentioned) perfectionism, his smooth camera moves designed to surgically attach our eyeballs to the actions of his characters. But this is all surface level stuff, and if The Killer were merely beautiful it would probably add up to nothing more than a fun time. But Fincher’s a devious man, a truly diabolical sort, and so of course’s there more to The Killer than meets the eye. I’ve seen some people dismiss this thing as nothing more than a stylish exercise. Those people are wrong.

The Killer, as it turns out, is more of a satire of 21st Century Stupidity than almost anything else. Muscle bros, McDonalds, children, blind optimism, Amazon Prime shipping, even Fassbender’s titular assassin…none of them are free from Fincher’s (and writer Andrew Kevin Walker’s) impossibly dry wit. This is a very funny movie, almost funnier than it is thrilling. Almost. Luckily it’s also a perfectly-pitched thriller, a tension-builder of the highest order, clearly and consisely setting up its dominoes before taking great joy in watching how Fassbender knocks them all over. But what really sends this over the top, and what clinched its inclusion on this list, is its sense of loneliness. Fincher might not have dedicated as much of his career as either Michael Mann or Martin Scorsese (two names that’ll pop up again soon…) to excavating the gaping cavaties that exist in masculine hearts, but all one has to do is watch the film’s best scene, where an icy Tilda Swinton questions the motives of Fassbender’s guy, to be left with the implications of how horrifyingly empty some people are.

Like the song says: “I am human, and I want to be loved…just like everybody else does…”

#6: John Wick Chapter 4 (dir. by Chad Stahelski)

I’m paraphrasing here, but Brad Bird once said something like this: “I love all artforms, but I love film the most because it combines so many of them”. It’s just my humble opinion, but I think the best films tend to represent that kind of synthesis Bird was talking about. What do we remember from great movies? Don’t we remember everything? We remember dialogue. We remember the pretty pictures. We remember the music. We remember the performances. We remember movement, sound, speech, rhythm…and when a movie can combine all of these things in their purest forms, a sort of esctasy tends to rise out of the mix. John Wick Chapter 4 is one of those special movies that combines all of those seperate arts, and indeed produces that resulting esctasy. It’s what Roger Ebert might’ve called “pure filmmaking”, dedicated solely to pushing the limits of its own self, a beautiful body dancing perfectly to its own tune. Director Chad Stahelski, star Keanu Reeves, and DP Dan Laustsen have been using most of the past decade pushing the limits of the American action film through the punishing stories of John Wick, and now it’s arrived in its most perfect, most ridiculous, most stimulating form.

But, like so many other movies that made this list, John Wick - Chapter 4 justifies its immense handsomeness by being about somebody who is forced to reckon with the fact that, if there is indeed a Heaven, they are most certainly locked out of it. Unlike this year’s The Equilizer 3 (hey, everyone at Sony: you totally blew it by not calling it The Threequilizer), which pretends that Denzel’s Robert McCall, a man capable of immensely violent acts such as stabbing a guy in the eye with a revolver and then shooting through his brain-pan to kill another guy behind him, is fully deserving of a peaceful ending….Stahelski & Reeves know better. Actions must always have consequences, even in movies where everybody is a sharply dressed master of hand-to-hand combat. There must be weight to these things, and John Wick - Chapter 4 is (thankfully) saddled with that weight.

Also: this is the only film this year, that I’m aware of, to feature an extended sequence where hapless hitmen are ping-ponged around a traffic-heavy Arc de Triomphe like a level from Frogger.

#5: Ferrari (dir. Michael Mann)

It is a terrible thing to been head-over-heels in love with something that is completely incapable of ever loving you back. Baseball, while enormously entertaining, all too frequently breaks the hearts of its passionate fans. Italian cooking has a habit of returning the affection it receives by gifting love handles. You can talk to a movie all you like, but it will never talk back to you. Race car driving is much the same, or at least that’s what it would seem Michael Mann is trying to say with his newest masterwork, Ferrari. Like nearly all of Mann’s movies, Ferrari tells the story of an inconsolably lonely man who attempts to fill the holes in his life with a singular obsession. In this case, the lonely man is Enzo Ferrari (Adam Driver), and the singular obsession is building the perfect automobile and winning races with it. The film takes place in 1957, with Ferrari caught in a hurricane of his own making: his company is on the brink of financial ruin, his wife Laura (Penélope Cruz) has discovered that he has a secret son with mistress Lina (Shailene Woodley), and he is betting everything he has on his team winning the dangerous Mille Miglia race. What follows is an extraordinary film, showcasing new angles of its creator while still remaining unmistakably his.

Don’t let the sheet metal, sharp Italian suits and roaring engines fool you: Ferrari is a movie with a yearning, burning, screaming heart far beyond masculine posing and fast cars. This is not a movie built to make your dad laugh, or to make your uncle want to subscribe to MotorTrend. This is a disection of a human being, the unmasking of a man who uses affairs, thick sunglasses and four-wheeled rockets to disguise the pain eating away at him. To watch Ferrari is to watch a man’s life be interrogated, his passions wrecked, his faith in the universe shaken over and over and over again. Mann asks questions most ignore when taking the Great Man Biopic Road. Why do we so often attach ourselves to dangerous pursuits that threaten our lives? Why do we so frequently hurt the ones we love? Is it to make ourselves feel alive? It is in the vain hope that maybe, just this once, we can gain some measure of control over our fates? Michael Mann doesn’t answer those questions in Ferrari; nobody could with any film. But he asks them, and then he fills the sound mix with those roaring engines; if you’ve ever had something you’ve been willing to dedicate your entire life to, you can’t help but hear the cries of your destiny within the screams of those machines. And then you understand.

#4: Maestro (dir. by Bradley Cooper)

“You know my mind.”

I recently had somebody say those exact words to me in the middle of an incredibly fraught conversation: “you know my mind”. I answered by saying I didn’t, that I would never be so arrogant as to assume I knew what they were thinking. But then the rest of the conversation unfolded exactly how I imagined it would, and then the days that followed unfolded exactly how I imagined they would, and I eventually I realized that they were, as they had so often been, absolutely right. I knew them better than I even wanted to admit, because to know somebody, to truly know somebody and to let them truly know you, is to expose yourself to the possibility of incredible pain. But it can also be a path to incredible joy; to be able to finish their sentences, to make them bust a gut with jokes nobody else would laugh at, to bring them to tears with a single sentence that wouldn’t mean a thing to a stranger. It’s an odd, incredibly tangible intangible. It rocks, and it also truly sucks.

There are multiple scenes in Maestro where Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan), actress and wife of legendary conductor Leonard Bernstein (Bradley Cooper, who also directs & co-writes), states with abosolute confidence that she knows her husband down to the molecules in his bones. She knows that “Lenny” isn’t straight, that he likes to have affairs with men, that he’s enormously self-absorbed, that he’s willing to grasp the hands of male lovers in public while she sits right next to him. Eventually it all becomes too much: she spits fire in his face once he becomes “sloppy” with his infidelity, and in return he abandons their family for coke-fueled parties. It’s immensely painful; they hurt each other simply by existing apart from one another. And yet, she knows his mind, and he knows hers. They know each other too much to be rid of each other, their paths eventualy colliding once more, their gravitational fields pulling towards each other even when death eventually stands between them. The connection between Mulligan and Cooper is so palpable, so delicate, that every time the movie threatens to shatter it I had a physical reaction to it. I teared up twice during the film, the first time when Felicia forgives Lenny by showing up at his legendary Ely Cathedral recording of Mahler’s 2nd Symphony; all her husband can do is embrace her, kiss her, look at her with the most thankful eyes. The second time was when Lenny cancels an appointment late in the film to stay with Felicia as she slowly wilts away from cancer. He then grabs a pillow and screams into it, realizing that there’s nothing he can do to stop the love of his life from leaving him forever.

By making Maestro, Cooper has done one thing above all. Yes, he’s demonstrated his immense filmmaking talents once again, proving that A Star is Born was no accident. And yes, he’s introduced a whole new generation to the genius of Leonard Bernstein, one of the greatest musical minds in American history. But above all else, he’s told one of the most heartwrenching love stories I’ve ever seen. To a degree unlike any other film I’ve ever seen, Maestro captures both the soaring joys and the scalding pains of truly knowing another person. For that alone, it is a triumph.

#3: Killers of the Flower Moon (dir. by Martin Scorsese)

Martin Scorsese, rarely a calm filmmaker, is in perhaps the most stoic, meditative period of his career as he crests into his eight decade of living. Fittingly, there is a tangible stench of death that surrounds his latest work, Killers of the Flower Moon, a true-crime film about the 1920’s Osage Murders, where over sixty members of the immensely wealthy, Oklahoma-based Osage tribe were murdered by white men in a plot to steal the “headrights” to their oil-rich land. Some of these killers were family to their victims, legally tying themselves to the land as spouses before murdering their “loved ones”. Leonardo DiCaprio plays Ernest Burkhart, one of the co-conspirators in the plot, and husband to Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone). His uncle is William King Hale (Robert De Niro), a rich man who seems fully aware that his grip on wealth is destined to fade as the future arrives and the world diversifies. And so, he ropes his nephew into a plot, convincing Ernest that he’ll need to somehow eliminate his own wife and inherent her land before the authorities catch on to what they’re doing.

This is a remarkable film made by the master of guilt-ridden crime stories. Over the course of his career, Scorsese has been tailoring a zig-zagging, violent History of American Filth: Goodfellas, Casino, Gangs of New York, The Wolf of Wall Street, The Irishman, and now Killers of the Flower Moon. This one might not be his most electric, or his quotable, but it might be the most impactful. Words like “important” are over-used when describing movies that deal with social issues or unfairly ignored historical events, so I won’t use it here even though I think every single person in this country should take it upon themselves to watch Killers of the Flower Moon and gaze into the maw of America’s horrific, genocidal past. But this isn’t a movie obsessed with lecturing, because the movie aligns itself too closely with a guilty person to climb on a higher horse. That person is Ernest Burkhart, as puzzling a subject as anybody I’ve ever seen in a motion picture, a man who tries to split the difference between his desires and his responsibilities and comes up horribly short. Scorsese, an outspoken Catholic, has always been fascinated by sinners who try to carry the weight of their mistakes on their shoulders. I believe he’s found his match with Burkhart, a man who evades reaping what he’s sowed until it’s the only thing he has left to do with his miserable life. To make a movie from this perspective, to depict a terrible person with such unblinking honesty, is an act of total bravery. Even better: it totally pays off.

I don’t care how long this movie is; you must see it.

#2: The Bear Season 2 (dir. by Christopher Storer, Joanna Calo, Ramy Youssef)

As many who know me can confirm, I have a chronic habit of waiting for the other shoe to drop…even if there is, by all accounts, no other shoe that is ever going to drop. There might not even be a first shoe, but there I am, waiting for that second shoe to fall from the sky and smash into my skull. Living with anxiety, and living with the belief that you don’t deserve to be truly happy, are curses that very few pieces of modern media can ever truly capture in their essence. Which is why The Bear is such a miracle, as it not only captures the exact (and I mean exact) feelings of those twin curses, but also strives to work through them with us.

The second season of the show is much like the first, continuing the hilarious, terrifying trials of head chef Carmy Berzatto (Jeremy Allen White), second-in-command Sydney Adamu (Ayo Edebiri) and manager “Cousin” Richie Jerimovich (Ebon Moss-Bachrach) as they attempt to (a) turn their sandwich shop “The Beef” into a fine dining establishment called (fittingly) “The Bear” and (b) try to find consistent happiness in a world that refuses to grant any breaks. And what a journey it is: I found myself laughing, cheering, punching my couch in frustration, and dissolving into a puddle of tears at various points during the season’s ten wonderful episodes. I don’t know any TV series that has ever stabbed me in the chest this deeply, that has ever made me feel as if electricity was coarsing through my veins, that had ever taught me lessons this succinctly without ever pandering. This is the best show of the still-young 2020’s, and its not even close.

#1: Oppenheimer (dir. by Christopher Nolan)

There’s a stretch of New Mexican desert known as the Jordana Del Muerto, which roughly translates to “Dead Man’s Journey”. On July 16, 1945, at precisely 5:29 in the morning, a light went off in the middle of the Jornada del Muerto. The light was called “Trinity”, a reference to a verse by the poet John Dunne: “Batter my heart, three person’d God”. But the light was not divine in the least; a group of scientists and U.S. Military personnel had just detonated the very first nuclear weapon. It was the culimination of years of work, the climax of the Manhattan Project, initially started in an effort to beat the Nazis in a race for atomic weaponry before the pivoting towards ending the war in the Pacific. Trinity gave way to Fat Man & Little Boy, two atomic bombs that the U.S. Air Force dropped later that summer over the densely populated Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While an exact number is impossible to calculate, it is estimated that over 220,000 people were killed as a result of those two bombings. In the years that followed, the work started by the Manhattan Project inspired a nuclear arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. Both countries stock-piled warhead after warhead until they were capable of annihilating human civilization as we currently know it. And that is the world we live in today.

Christopher Nolan was playing with a dicey hand when he decided to make a film about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattn Project’s director widely given credit for the atomic bomb’s existence, and therefore widely given further credit for having helped placed the entirely of human existence on the perpetual precipace of destruction. Oppenheimer was a brilliant man, like most subjects of Hollywood biopics, but his legacy is easier to count in bodies buried and bombs built than in the lives he actually improved through his work. What makes Oppenheimer great, or at least one of that things that makes it great, is how it embraces all sides of the man at once. It doesn’t shy away from the contradictions; instead it revels in them, using his inexplicably contrasting qualities as dramatic fuel. It doesn’t shoot its subject as a gorgeous, God-like figure: so often Nolan frames Cillian Murphy (who will win the Academy Award for this film, and deservedly so) like a man facing a firing squad, his eyes boring into the space just below the barrel of the 70mm IMAX camera, like a man who knows exactly how terrible his crimes are.

This is a movie that feels like it contains everything. It’s a totemic, towering thing…and yet, somehow, it has a miraculous focus to it. The film is structured not around Trinity, but around a security hearing that occurred about a decade later, orchestrated by politician Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr, who will also win a very deserved Academy Award for this film) in an attempt to skewer Oppenheimer’s reputation out of pure malice. Time is a funny, malleable thing in almost all of Nolan’s films, but here it plays out like a memory. Questions lead us back in time to answers, which in turn only lead to more questions, asked with increasing irritation as it becomes clear that the hearing is rigged to punish Oppenheimer…and that he feel he deserves it. Never before has Nolan ever examined a main character so mercilessly; maybe that’s why I’m so impressed.

Like all great character studies, Oppenheimer takes the form of its subject, mimics him. It’s contradictory just like he was (an epic film setting its most emotional scenes in a tiny, colorless room? A war film in which not a single bullet it fired?). It’s brilliant, just like he was. And, just like he was, it is saddled with the knowledge that his greatest creation might have set us on an inevitable path towards self-destruction. This is, in my opinion, the best 2023 had to offer: a Dead Man’s Journey, constantly looping back in time for answers and clarity, yet always finding itself in the present, the only knowledge gained being that it was probably always going to turn out this way.

Good list, I saw most and was pleased to see some Golden Globe recognition, especially for The Bear. Goes without saying this was beautifully written👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻👏🏻

List is solid and well reasoned —or emotional responses explained, as case may be…

I especially appreciate how you have included small screen work (Bear & Usher) in here, in recognition that this is how we live now.

Happy New Year, and I am looking forward to what you will share with your eager readers!