DISCLAIMER: the following contains some mild descriptions of self-harm.

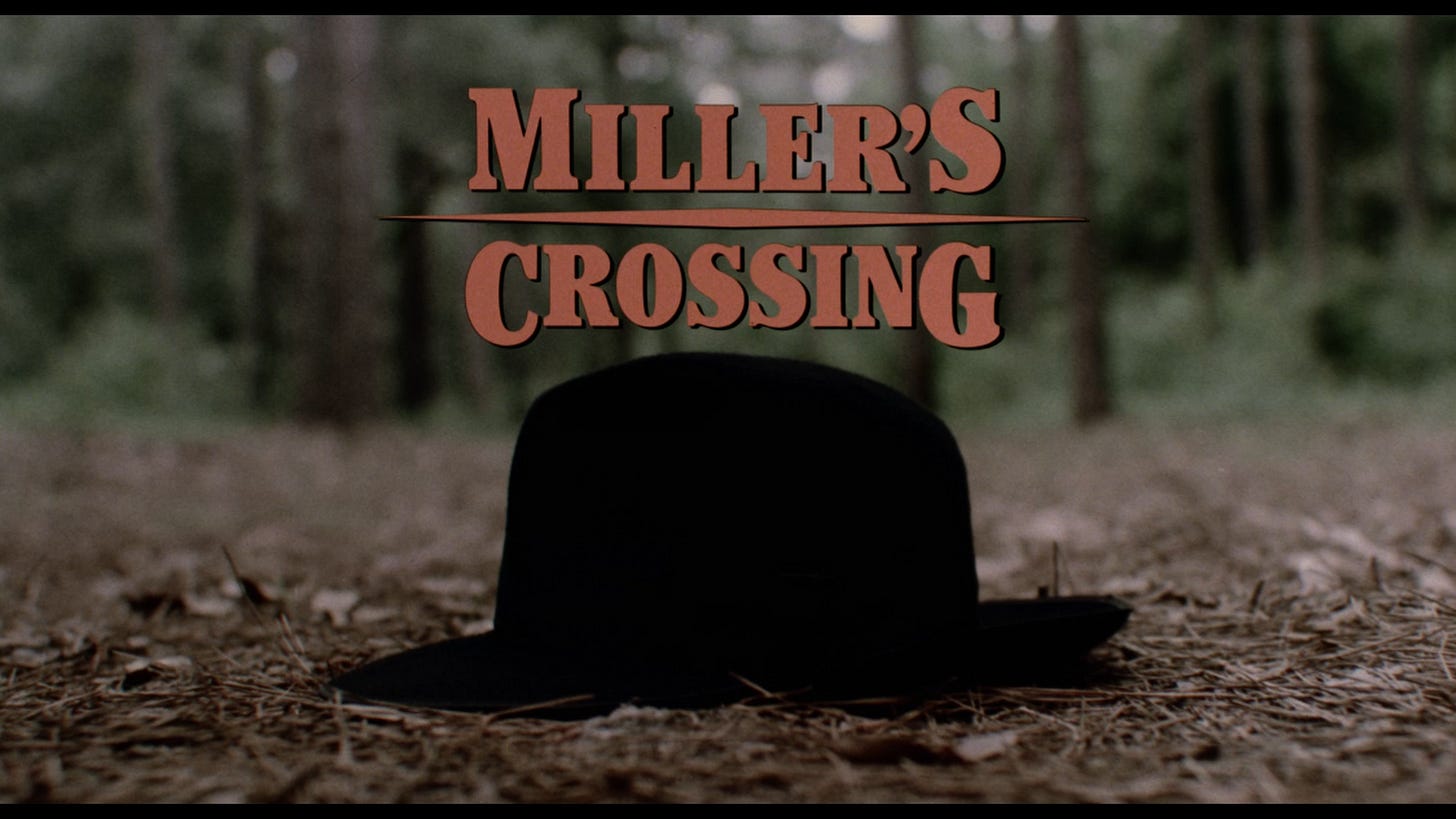

When I’m really anxious, I can’t sleep. And when I can’t sleep, I put on Miller’s Crossing. Perhaps in the absence of dreams, it’s only fitting that I turn to a movie so sneakily dedicated to feeling like one. Large slabs of it take place at either night or in the wee hours of the morning. It’s setting, both the where and the when, are kept intentionally vague. The violence is cartoonish, complete with great flowing squibs and thunderous foley noises, and yet there’s a great plaintiveness that haunts every scene. The opening credits play over a gorgeous, near-whimsical montage of soughing trees stirring in the wind, ending with a hat that falls into the middle of the frame before a wind blows it into the distance. Only later is it revealed that the scene was itself a dream, had by the film’s main character, Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne). When his lover Verna (Marcia Hay Harden) opines that the hat “turned into something wonderful” when he chased it, something symbolizing his innermost desires, Tom refuses to conclude anything so romantic. “No, it stayed a hat and no, I didn’t chase it. Nothing more foolish than a man chasing his hat.” Maybe it’s the romantic in me, but are few things more enticing at five o’clock in the morning than the life not lived.

From it’s opening, Miller’s Crossing establishes itself as a film whose native tongue is only a couple steps removed from complete gibberish. Irish mob boss Leo O’Bannon (Albert Finney) is being lectured to by rival Italian mob boss Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito) over drinks. Words like “vig”, “combine”, and “schmatta” are thrown around like frisbees; phrases like “take your flunkie and dangle” are expelled as casually as breaths of air. The subject eventually becomes clear: Caspar wants a bookie named Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro) killed for making money off of his fixed boxing matches. Caspar keeps mentioning “character” and “ethics”, clouding his obvious anger in oak-paneled words to delude both himself and Leo into forgetting that he’s just a mean crook who wants to kill another crook because his feelings are hurt. Leo, lovesick over Bernie’s sister Verna, tells Caspar “no”, prompting Caspar to leave in a fit of rage. The film largely proceeds forth in such a manner: miserable criminals walking into very large rooms, talking in circles around what they actually want, then eventually exploding when they don’t get it, all while saying shit like “what’s the rumpus?”. Nobody’s happy, and it’s everyone else’s problem.

To summarize the plot of this film would be a foul’s errand, it’s pretzel-like twists as maddening as its lunatic language. Basically, the Coens took two Dashiell Hammett crime novels and stitched them together: The Glass Key, the story of a political boss’s second-in-command who helps steer his employer through a violent crisis, and Red Harvest, the story of an unnamed detective who plays two mob sides against the other until everybody’s dead. Miller’s Crossing, fittingly enough, is the story of a political boss’s second-in-command who helps steer his employer through a violent crisis by playing two mob sides against the other until everybody’s dead (mostly). These influences have plagued the film’s rep ever since it came out; even if you’d never read a Hammett book or seen a Jimmy Cagney picture, it’s hard not to get the distinct impression that somebody’s driving with directions. There’s plenty of pleasure to be gotten from these shiny surfaces, to be sure, what with all the machine-gunning and fist-fighting. But for all the snappy dialogue and “didn’t see that comin’” plot yanks, I can assure you that absolutely none of that shit matters. It doesn’t matter why Bernie scams everybody, it doesn’t matter whether Verna loves Leo back, and it certainly doesn’t matter what Steve Buscemi’s doing in this movie. The only thing that matters is Tom.

In a sea of professional fools and halfwit heroes, Tom Reagan is a Coen Brothers protagonist unlike any other: he’s unequivocally cool. He dresses immaculately. He speaks in a dark, mocking, sing-song lilt. He drinks whiskey like tap water. He’s the second in command to Leo, his confidant, his best friend. He’s a freak in the sheets (something that applies to almost zero other Coen characters). And he’s always, without exception, the smartest person in the room…which is good, because the film wouldn’t work if he wasn’t. Aside from Bernie’s annoying backstabs, almost all of the plot swings hinge on Tom’s ability to convince whoever he’s talking to that he’s not utterly full of shit. Sometimes he’s telling the truth, like when he gets purposefully excommunicated from Leo’s gang after admitting he’s been sleeping with Verna on the side (more on that later). Sometimes he’s lying, like when he convinces Caspar that not only did he kill Bernie for him (he didn’t), but that his loyal henchman Eddie “The Dane” Dane (J.E. Freeman) is trying to take the throne for himself. In a town filled with violent thugs trying to one-up each other, and in a filmography of absent-minded morons, it’s Tom and Tom alone who plans more than a single step in advance.

Alas, the Coen Cynicism is too strong, their self-awareness too total, to let Tom off the hook completely. For a “professional gambler”, Tom’s absolute shit at it, spending most of the movie dodging a leg-breaking bookie named Lazarre he owes an ever-growing amount to. His rotten luck goes beyond betting; no more than zero of Tom’s ideas goes off without a hitch, the idiocy/tenacity of others causing him to wing it more times than not. And, in one of the film’s best running gags, he has a habit of getting the absolute shit knocked out of him. Leo punches him, Verna punches him, a little grey-haired guy named “Tic-Tac” punches him; during the climax, the Dane hits Tom so fucking hard he literally flys backward. He’s also tripped, kicked in the head twice, thrown down multiple flights of stairs, strangled, slapped, hit with a purse by an old lady, and gets a shoe tossed at his head for good measure. In return, he breaks exactly one nose with one chair, and kills exactly one person with one bullet (again, more on that later). Funnily enough, while other characters comment upon Tom’s knack for bodily harm (the Dane calls him “Little Miss Punching Bag”), he himself never complains. Not about his debt, not about his luck, and not about the dozens of concussions he doubtlessly sustains over the film’s runtime. Tom seems to take it all in stride, as if even he knew he had it coming.

Part of Miller’s Crossing charm is its infinite rewatchability. Not because of the language, or the twists; it’s because of the giant mystery it makes of its main character. For all of the ambiguities and loose threads peppered throughout their movies, Tom Reagan himself is probably the ellusive question mark the Coens have ever drawn. Everything he does is a puzzle. Never once is it explained why he tells Leo that he’s seeing Verna, why he defects to Caspar, why he decides to blow up Caspar’s empire, why he spares Bernie’s life the first time he’s pointing a gun at him, why he doesn’t the second, and why he ultimately decides to step away from both Leo and Verna’s life in the end, despite an earnest offer to be a part of it. He’s methodical and impulsive and determined and driven…but to what end? Most viewers seem to conclude that Tom had it all planned from the start, that he was always going to help Leo out by destroying his nemesis, that he was always going to help Verna out by destroying any reasons to stay with him. When Leo posits the theory himself at the film’s end, Tom makes clear that he’s not so sure. I’m not either.

There are few pastimes more sorry, and more dangerous, than self-hatred. It’s a seductive, cyclical thing that only requires a thought bad enough for doubt to creep in; give the doubt enough weight and it’ll start to develop its own gravitational pull, a black hole that can suck up an entire person if left unchecked. Results may vary, but self-hatred can often lead to self-harm. Over the years, I myself have scratched and clawed at my own skin, slapped my own face, yanked at handfuls of my own hair, hit myself with small objects, etc. Nothing too damaging, but certainly not the kind of thing you mention at parties. Self-destruction is another symptom. Oh, how easy it is to receed into one’s self, to burn bridges, to cut off friends, to lash out at loved ones for daring to cherish you and accept you. “What fools they are to believe in me”, you think. “They don’t know I deserve this”, you think. “They don’t know the things I’ve done. They don’t know the person I really am.” Maybe if you hurt them enough times, maybe if you show them who you really are, at least you can do them the favor of being honest. And if they leave you, isn’t that a good thing? Aren’t they better off?

For all the whiskey and fiddles and playing of “Danny Boy”, the most Irish thing about Miller’s Crossing is its guilt-ridden familiarity with self-hatred. It pervades every fiber of Tom’s being. He reeks of the stuff, especially whenever he wakes up from a night with Verna, never failing to sit contemplatively at the edge of his bed, the stub of a cigerette burning away in his hand. It’s a strange, Don Draper-like affliction; if you were to take a shot for every scene in which Tom is amused by his own intelligence you’d be dead by minute thirty, but left to his own devices the man seems obsessed with finding new & exciting ways to self-immolate. Why else would he turn down three seperate opportunites to earn enough money to pay Lazarre, if not because facing the physical punishment is easier than asking somebody for help? Why else would he engage in a torrid, hateful affair with Verna, if not to piss off the person he loves most in this world, to reject the love that he feels he doesn’t deserve? And why else would he kill Bernie, the brother of the woman that cried over him that very night, if not to definitely prove that he really is as bad as everybody keeps saying he is, as he probably believes he is?

For me, Tom’s actions speak for themselves. In the film’s final scene he, in quick succession: shows up late to Bernie’s funeral, cracks a joke about the lack of mourners to a grieving Verna, offers an obviously insincere “Congratulations” at the news of Leo’s engagement, refuses to acknowledge that his actions were intended to help Leo, refuses to reunite with him, rejects an apology, then says goodbye to his only friend forever. It might be the most nakedly sincere sequence the Coens ever concocted; the hero openly tossing away the possibility of a happy ending for a sad one, going out of his way to alienate the only two people he gives a shit about. And for what? Most would probably shrug and chalk it up to Tom’s eternal enigma; to quote another Coens’ film, “It’s a fool that looks for logic in the chambers of the human heart”. But as Tom leans against a tree, places his trademark fedora on his head, and stares out into the distance at Leo walks away from his life forever, we realize he’s back in the place of his dream. Only the hat is not a hat at all but a person, a person he loves. But Tom, true to his word for better or for worse, refuses to give chase. The life not lived, truly.