They say comparison is the thief of joy, and I know they say this because I’ve had more than one friend utter those exact words to me over the past week. I guess one of the reasons I needed to hear it is because I was once, and occasionally still am, a very jealous person. I have no idea why. I have a lot to be grateful for. I’m a lucky guy. I have friends who like & respect me. I have a talent that makes me happy and excites others. I have my health, my hair, a good jawline, and cool blue eyes. My apartment has a grand total of zero cockroaches…and yet. Maybe it’s a writer thing; it’s weird to be good at something that, theroetically, every single member of the human race could learn at any age and become good at (it’s really just a cocktail of critical thinking, typing, and being a smartass). It’s not like this is ballet. Maybe it’s a trust issue thing; that I feel the need to keep proving myself to my friends to avoid the irrational fear that they’ll discard me like that meme from Toy Story. Maybe it’s a baggage thing, my brain having yet to dump all of the bad lessons I learned in high school. Then again, maybe it’s “no” thing. Maybe it’s just my brain’s method of keeping me on edge, keeping me on top of things, keeping me from getting too comfortable. I wish I weren’t ever jealous. Not that you asked, but I happen to like myself quite a lot. And yet…

The most important line in The Social Network, a movie you’ve probably heard of, arrives less than one minute into the film’s two hour runtime and is spoken by one of the film’s only important female characters (there are are grand total of three, all of them supporting at best). The line is: “On the other hand, I do like guys who row crew.” Every other line of dialogue in Aaron Sorkin’s glorious, beloved, incredibly influential, acclaimed, ripped-off-to-Hell screenplay is less important than that one. Everything from “You have part of my attention, you have the minimum amount” to “If you guys were the inventors of Facebook, you'd have invented Facebook” to “At the moment I could buy Mt. Auburn Street, take the Phoenix Club, and turn it into my ping-pong room”, and all those other Sorkin-y slices of talky-talk speaky-speak are almost irrelevent. They’re catchy lines that fit well in the film’s very good trailer (set, very aptly, to a song that includes the lyrics “I want you to notice when I’m not around"). They’re lines that look good on a poster, and sound good out of your most annoying friend’s mouth even as they slur them in-between breaths that smell vaguely of Pabst Blue Ribbon. They also have absolutely nothing to do with what The Social Network, one of the most famous and most influential films of our very young 21st Century, is actually about.

Why do people like The Social Network? I know several people who consider it among their favorite movies, to the point where entire chunks of the damn thing seem to be stamped onto their brain matter, giving them perfect recall for each one of director David Fincher’s impossibly-smooth camera moves. I love the movie too, to be clear; there’s no confusion on my part for why people like it. It’s among the smoothest two hours ever committed to film, each scene flowing along like a white-water river on a clear summer’s day. There’s a rhythm to it, a cocktail of Oscar-winning writing, Oscar-winning editing and Oscar-winning music that makes you bop your head and tap your feet to the film as if it were a 70’s disco mix. And I’m sure the constant, male-centric, multi-page monologues are another reason for its place as a Film Bro cornerstone. It’s the trademark of all Sorkin trademarks: watch this smartass white dude riff endlessly about how smart he is in front of a bunch of doubters, watch them tremble at the sight of this smarmy genius and his brilliant brain. These were the reasons I liked the movie back in high-school (big shock: I was a smarmy wannabe-genius who really wanted to make others tremble at the sight of me and my not-so-brilliant brain). They’re not the reasons I like the movie now. And so I won’t be talking about them for the rest of this newsletter (there’s plenty of writing on those things you can find elsewhere). Instead I’ll be talking about why I like The Social Network.

There are pros and cons to having the same talents as your friends. The pros: you will make a lot of fruitful, sometimes beautiful, personal connections with the people in your life. You’ll always find something new to talk about, new jokes to laugh at and new stories to share. The conversation tank rarely runs dry if you love what you do and they love what you do, because love never gets boring. You might even get to the point where you’ll work with your friends, and there are few things more fulfilling than working with your friends. The cons: you will spend ungodly amounts of time comparing yourself to your favorite people in the world, and it will rip you apart. You won’t get the reassuring distance that I have when I see pictures of Timothee Chalamet hanging with the Knicks cheerleader squad, because I’m never going to meet Timothee Chalamet (and at least I’m taller than he is). If you’re a good person, you'll probably spend a lot of time complimenting your friends, often by disparaging yourself in comparison. They’ll sound like this: “Oh wow, I could never do something like that!” or maybe “Man, I wish I had come up with that!” Sometimes you’ll be lying when you say these things. But sometimes you’ll be telling the truth, probably more often than you expected. Don’t let anybody ever tell you art isn’t competitive. It’s just a pain in the ass to be racing against the people you love.

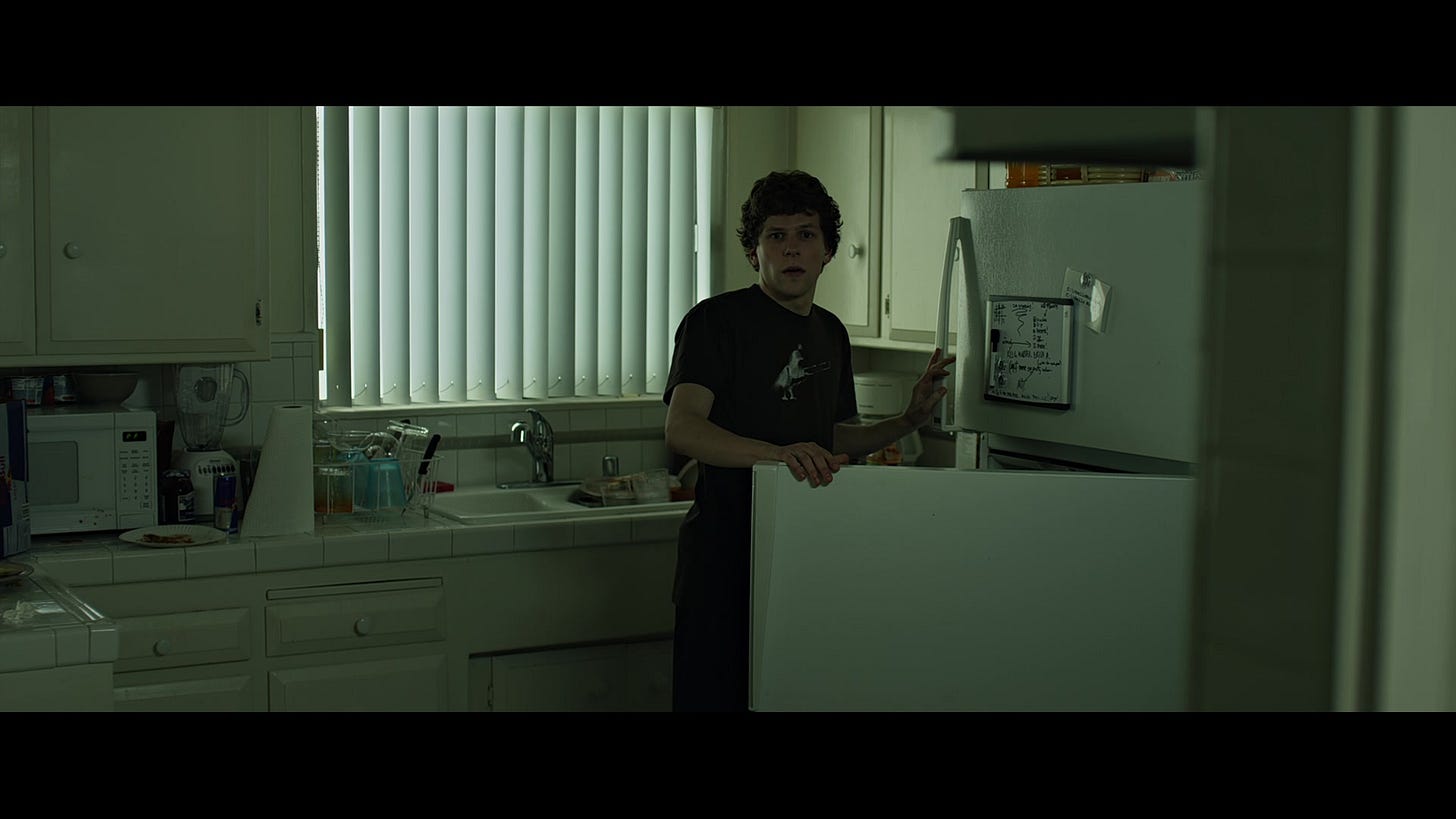

For something that’s about the creation of a tech company, there’s probably no major American feature film as obsessed with the unimaginably boring subject of prestigious college clubs as The Social Network. It seems to be all that Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) ever thinks about. He brings it up in the film’s opening scene with his soon-to-be-ex Erica (Rooney Mara). He brings it up when he steals the idea of Facebook from the Winklevoss twins (Armie Hammer & Josh Pence). It even gets brought up in the bitter, rage-driven depositions that frame the story, years after college stopped mattering to the youngest billionare to ever live. But he never really brings it up with his best friend Eduardo (Andrew Garfield), because Eduardo brings it up with him. Because he’s in one and Mark is not. The jealously is obvious, even as Mark tries to hide it behind his stoic face and the sound-barrier-breaking speed he speaks in. When Eduardo humble-brags to Mark about having passed the first step to entering Harvard’s Pheonix Club, Mark simply says: “You should be proud of that right there. Don’t worry if you don’t make it any further”. And then he immediately returns to whatever he’s doing, leaving his friend to soak all that up on the other side of the room. And when Eduardo inevitably gets screwed over by Mark by having his company shares unjustly diluted, he throws it all the final club crap right back at former best friend’s face. Mark feigns ignorance through anger. It’s not convincing.

That’s not to say that The Social Network believes exclusivity can make people happy. Take the Winklevoss Twins, Mark’s self-made nemeses. They’re handsome, rich, Olympic-level rowers that belong to one of those stupid Harvard clubs Mark keeps pining for (one so elite they can’t allow non-members pass the entrance’s bike room). They also spend the entire movie miserable, angry and in perpetual 2nd place. Spoiler: they come up with the basic idea of Facebook themselves, pitch it to Mark before he did anything on his own, and then dedicate the rest of their plotline to gleaning money from the blatant theft. The problem: nobody wants to help them, because they walk and talk like entitled assholes who’ve had every iota of their lives served on silver platters since they popped out of their mom’s womb. They get the verbal equivalent of a round-house kick to the groin from Harvard President Larry Summers, who proceeds to dig their graves, piss on the dirt above, then salt the earth to make sure his urine won’t accidentally grow anything. But if you came up with an idea that good, an idea that was yours and yours alone, wouldn’t you want something to show for it? Wouldn’t you want to prove to others that there was something good in your life that didn’t come from daddy’s money? It doesn’t matter if their father’s proud of them (“Don’t ever apologize to anyone for losing a race like that”, he says after they actually come 2nd place at the Henley Royal Regatta). You can’t have your parents being the only ones who respect you; your pride won’t except it.

I walk a lot. It’s a good thing to do in a city with multiple colleges and a very long coast line. I see a lot of young couples on these walks, and sometimes I feel a twinge of something spikey when I see them. I wonder what they know that I don’t, and then I wonder why it’s still being kept from me. Sometimes it feels like everybody good and deserving passed some test I’m still trying to take, that I missed a boat they’re all sailing on (among other metaphors). I know it’s a stupid thing to believe, but sometimes you live with something stupid long enough you forget it’s stupid. Loneliness is a disease that breeds worse diseases, and complacency is one of them. But hey, at least I can write a pretty sentence about it.

I think it’s weird that Justin Timberlake is in this movie. I also think it’s weird that Justin Timberlake is very good in this movie (as fictional tech investor extraordinaire Sean Parker, a fictional amalgamation of the real Sean Parker and a bunch of people Aaron Sorkin was clearly less interested in), because he isn’t very good in that many movies. But he’s perfect as Sean. In fact, it’s possible that nobody was more perfect for this part than Timberlake. He’s a rock star to Mark, a Golden God of Silicon Valley who has seemingly everything the nerdy Facebook founder could ever want: style, confidence, good looks, charisma, a female companion clinging to each shoulder at practically every moment. When we meet him its in the bed of a 20-year-old Dakota Johnson, making her blush with his Timberlake-esque charm. But it’s all bullshit, because Sean is a bullshit artist of the highest caliber. Just in case you forgot: this isn’t a movie about happy, satisfied individuals. In one of the most clever reveals any movie has dreamed up, we learn that, despite his insaitable hunger for parties, Sean carries both an EPIPEN and an inhaler around that prevent him from actually ingesting any drugs. And those women he always seems to court? “How old are they, Sean?”, asks Eduardo as two of them take massive bong hits at command somewhere in the background; Sean declines to answer. Even his backstory comes from a place far, far away from the Land of Cool he seems to rule: he tells Mark that he created Napster to win over a girl that was dating the high-school lacrosse captain. Certainly no underlying issues there, no sir.

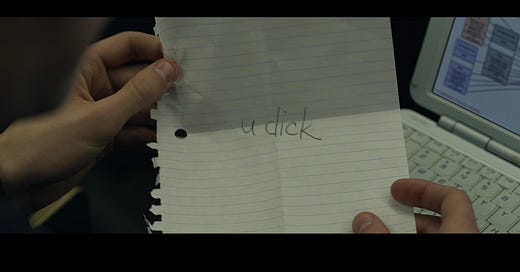

Mark doesn’t have the same kind of “luck” with women. He doesn’t have that many guys in his life either, but that doesn’t seem to bother him. The lack of women does. When Mark gets drunk & angry over Erica dumping him, he goes on a blogging tirade that culminates in the creation of Facemash: a gob-smackingly misogynistic site dedicated to comparing the hotness of female Harvard students. But as Mark types away on his computer, the film keeps cutting back to a party taking place at one of those final clubs. A literal bus of girls are shipped in, congratuated by some blazer-wearing assholes for having the honor of attending, and then spend the rest of the montage in various states of undress, playing strip-poker and downing shots. It’s never made clear if any of this is actually happening (none of the actors depicted show up again, and it’s all filmed like the world’s most expensive underwear commercial); it could just as easily be something our “hero” is angrily cooking up in his brain as he denigrates his ex on the internet, all that insecurity and objectification bubbling into the film’s digital negative. The only other time Mark talks to Erica comes much later, after Facebook has become enough of an online sensation that he’s having sex in bathroom stalls with near-strangers. He spies her across the room, instantly forgets about his NSFW rendezvous, and proceeds to make an ass of himself as Erica refuses to give him the time of day. Even after he’s reached the top of the mountain amidst Facebook’s millionth follower, Mark still finds time to feel small: look at his face when he asks Sean about the intern, Ashley. He can barely eek out a word.

The reason “On the other hand, I do like guys who row crew" is the most important line in The Social Network (at least for me) is because it seems to be the most important line of dialogue for the character of Mark Zuckerberg. He can’t let it go. “They’re bigger than me, they’re world class athletes”, he says. He badgers Erica on why she said it until both of them have forgotten what they’re even talking about. He seemingly moves on…until he meets the Winklevii, who just so happen to row for Harvard full-time. It’s takes a special kind of male resentment to keep beating on year-after-year, to mutate and metastasize when it should wither. And it takes a special kind of asshole to ignore warning sign after warning sign, to keep thinking that everybody else is the problem and that this next thing you do will finally let you beat them, that this next win will finally be the thing that makes you happy. But if there’s one thing I’ve learned from my experience with jealously, it’s this: all it ever did was waste time and make me a worse person. It does not inspire good art and it does not inspire good thoughts. The only benefit of knowing jealously intimately is that you might eventually learn how useless it is, and then you can move on. There’s nothing at the end of Fincher’s film to suggest that Mark, the Winklevoss Twins or Sean Parker will ever be able to move on. They’re young, sure, but they’re also rich. It’s hard to change a rich person’s mind about anything. The Social Network is a movie about embracing the worst aspects of yourself, and all the harm that’ll come if you do. Love and friendship are the most important things in the world; don’t let fear or self-hatred destroy them like Mark does. No amount of parties, Victoria’s Secret models, cocaine, money, or digital monuments constructed in your own image can fill the holes of deep-rooted insecurity. Not even a net worth that rounds up to $75 billion.

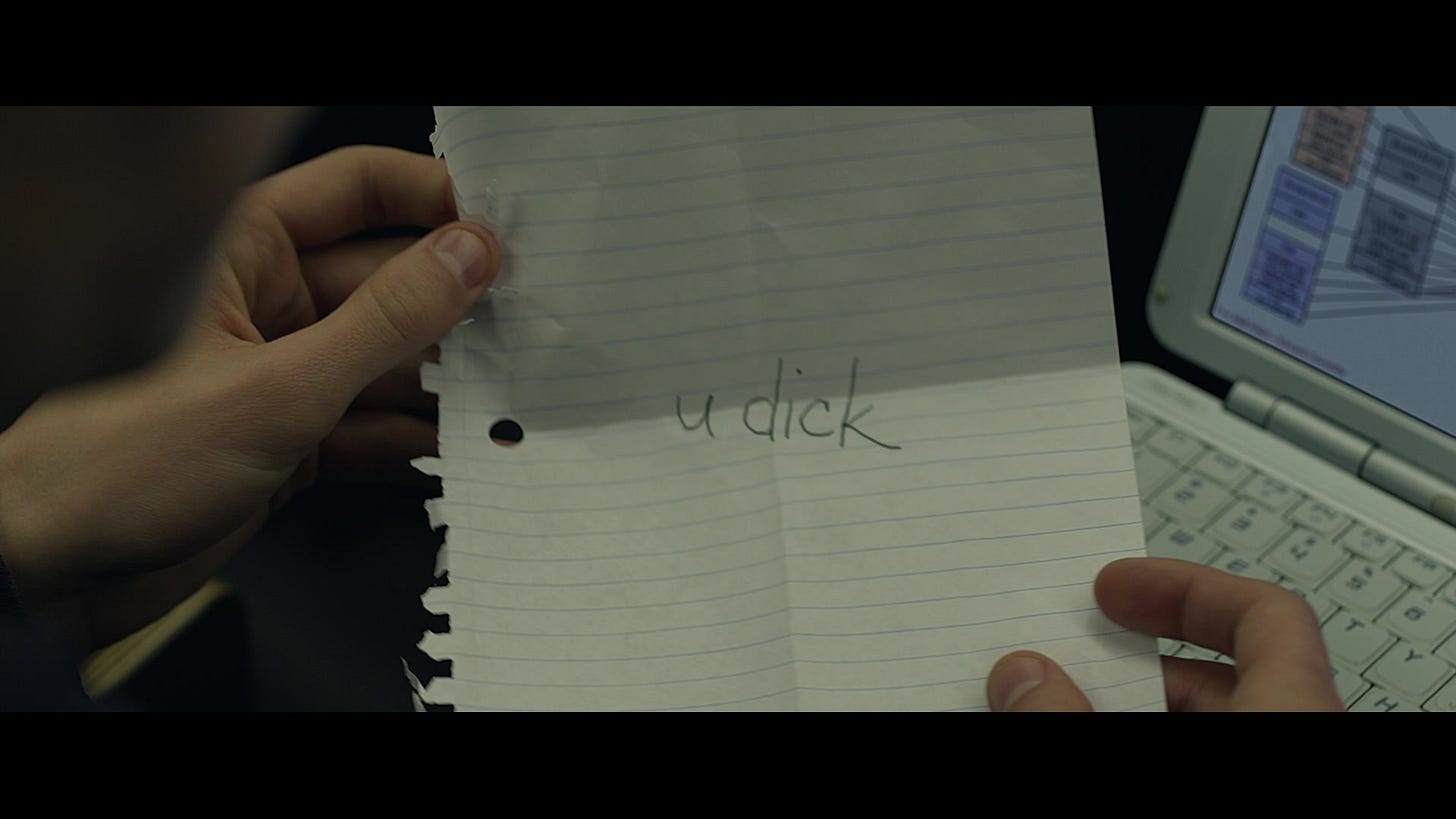

I’ll end this by talking about my favorite shot in The Social Network, a very pretty movie that has no shortage of very pretty shots. It pops up somewhere around the beginning of the third act, after Mark has moved to Palo Alto to get closer to the Bay Area’s tech industry. Sean and his um, “friend” Sharon (Emma Fitzpatrick) come over after discovering he lives across the street from Mark. Mark offers them a beer. He tosses one to Sean, then he tosses one to Sharon. The throw is bad misses and the beer crashes against the wall. Sharon apologizes, but Mark barely pays attention and just throws another one to her, as if he’s mimicking the kind of cool he always seens in movies. Sharon tells him to wait, but he doesn’t. His aim is even worse this time, and the beer smashes in the corner of a kitchen cabinet. Then Mark looks almost directly into the camera, maybe at Sharon, maybe at nobody in particular. He looks lost and sad, unable even in this very brief moment to be smooth or confident. He just stares, unable to process why he can’t just throw a beer into somebody’s hands like a normal person.

(The Social Network is available to rent on all major streaming platforms)

Very impressive review- and very well thought out- I will not hesitate to rent this movie 🍿 soon.

Yes, it surely is…